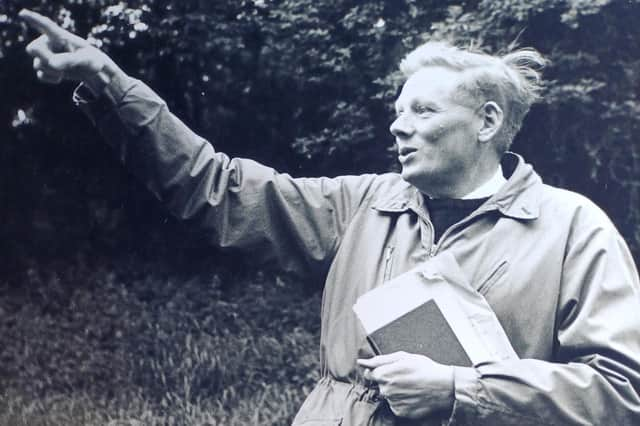

Scotsman Obituaries: Charles D Waterston, Keeper of Geology at National Museum in Edinburgh

Charles D Waterston may have spent his entire career at Edinburgh’s Royal Scottish Museum but his knowledge and influence spread far beyond the walls of the Chambers Street building. He collaborated with colleagues in Norway and South Africa, lectured on cruise ships and was an external examiner at Cambridge University.

In retirement he served as general secretary of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and pursued a long-standing interest in family history, leading to the publication of a book on his ancestors which he gifted to all living descendants.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdBorn in London’s Hampstead, to Martha and Allan Waterston, his father was the London director of George Waterston & Sons, stationers and printers of Edinburgh and London and the fifth generation of the family firm. Educated at St Mary’s Primary, Hampstead and then Highgate School, as a youngster he enjoyed holidays at his grandmother’s home in Perth, where he relished the freedom to explore the Scottish countryside and canoe on the River Tay at the bottom of the back garden. Those idyllic trips were the “very heaven”, he said, and fostered a lifelong interest in the natural world.

But the outbreak of the Second World War when he was 14 saw him evacuated to Westward Ho! in Devon before his schooling came to an abrupt halt when the family home in London was bombed and his father’s warehouse went up in flames. In 1941 he left school and the family all moved to Edinburgh.

There he attended Skerry’s College, gaining the Edinburgh University entrance qualification and intending to study chemistry. However, he failed in mathematics and joined the Royal Naval Volunteer Reserve under the Y Scheme for youngsters who were potential officer material. His bid to serve his country proved very brief – six weeks at HMS Ganges – when he was discharged after failing a medical, something he joked may have been for the best for both himself and the war effort.

Returning to university, he passed two years of chemistry but was so inspired by the teaching of geologist Professor Arthur Holmes that he then switched to geology and, on graduating with first class honours, won a scholarship enabling him to do a PhD in 1949. The following year he was appointed an assistant keeper in the Natural History Department of the Royal Scottish Museum, where he was to remain until 1985.

His diligence with the geological collections persuaded the authorities of their importance and three years later he found himself promoted to take charge of a new department of geology. Over the next few years he was elected a Fellow of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and invited to join the National Trust for Scotland cruises as a lecturer. On his first cruise, in 1961, he was thrilled to land on the abandoned island of St Kilda and The Shiants in the Hebrides.

The following year he joined the Trust’s adventure cruises as a lecturer and member of staff of the vessel the Dunera. It was at a packed service for the Dunera cruise in St Magnus Cathedral, Kirkwall, that he met his future wife, Marjory, a passenger. He was looking for a seat and she waved to indicate a vacant space next to her. She “sang like a linty” and the rest was history, he said. They married three years later.

Marjory was also asked to join the cruise staff and they sailed together on vessels for many years. She was a huge support to her husband, who had been promoted to keeper of the geology department in 1963 and often deputised for the museum’s director. She played hostess to many distinguished overseas scientists who visited his department and accompanied him on international assignments to Canada, the USA, South Africa and Norway.

Throughout his career and beyond he shared his passion for his subject, writing myriad papers, giving prestigious lectures – notably to Oslo University and the Cultural Department of the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs – and winning numerous awards, including the Bicentenary medal 1992 of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Geological Curators Group’s first A G Brighton medal for good curation and advancing geological science. In retirement his interest in the history of science and Scottish geologists resulted in various studies and the publication of his Collections In Context: The Museum of the Royal Society of Edinburgh and the Inception of a National Museum for Scotland.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdHe was also a professional adviser on a review of the Royal Commission on Ancient and Historical Monuments in the mid-1980s, contributing author to a 52-part series, Discover Scotland, in Mirror Newspapers, 1989/90, and later sat on the advisory committee on Sites of Special Scientific Interest. Around the Millennium he was chairman of the judging panel for Scottish Museum of the Year awards

In his leisure time he enjoyed music and singing, and he and Marjory climbed all 133 Donalds, hills over 2,000ft, south of the Highland line. Latterly she had Parkinsons and he cared for her up to her death in 2008, the same year he published Perth Entrepreneurs: The Sandemans of Springland, which stemmed from his boyhood fascination with Springland, a house near his grandparents’, and his great, great, great, great grandfather George Sandeman.

His interest in family history had been awakened by his grandmother’s stories of “the old days” and was later magnified by the discovery of historic documents in his great aunt’s deed box, including letters describing a relative’s experiences in the Napoleonic war. The end result from this modest, sharp and compassionate man was A Gift of Ancestry, The Family of James Dewar and Susanna Rattray, which was distributed to descendants in 2018.

He and Marjory had no children but he is survived by two nieces and two nephews and countless cousins, variously removed, around the world whom he discovered through his genealogical research.

Obituaries

If you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), contact [email protected]