How Dundee invented 'heckling' and once sent 'Tree of Liberty' to prison – Susan Morrison

In the National Museum of Scotland's digital display of banknotes and coins, there is a tiny copper token. It’s dated 1797, and was issued by a hemp importer. It’s stamped with the image of a worker and above his head it says “Flax-Heckling”.

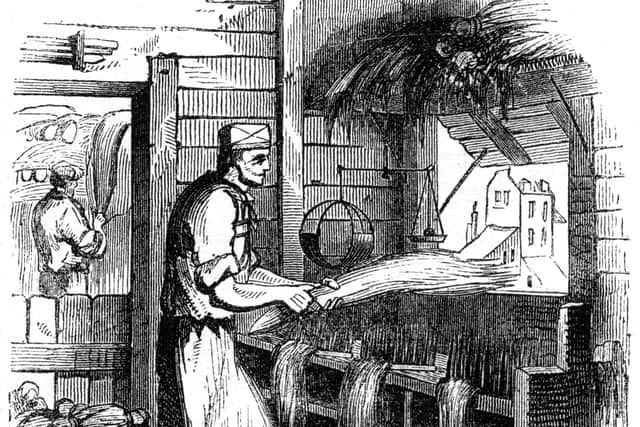

It’s concrete proof that hecklers and heckling are another globally famous product of the once-mighty jute mills of Dundee, and its radical workforce. Heckle is a very old word, much older than the jute mills. In the 13th century, it was ‘hechele’, the dressing of flax, the final step before weaving. The flax would be pulled through heckle combs to smooth and clean the fibres

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIt's simply an early industrial process, like weaving, threshing or grinding. So how did heckling take on a life of its own, and become the nemesis of politicians and comedians? Perhaps the answer lies partly in the job, where it was done, and the city of Dundee itself.

Dundee was already a centre for flax working when, in 1824, a linen-manufacturer called Anderson, got a hold of a few bales of jute. At first, he was flummoxed, but persevered, until they created a yarn of pure jute, and started to churn out the military uniforms, shipping sacks and cheap, tough cloth demanded by an expanding empire. Within a decade, the price of jute had rocketed and fortunes were being made. Well, by the mill owners, at least.

Les Dawson’s facial expressions

Soon the jute boom was attracting workers from all over Scotland and Ireland. They lived in appalling conditions. The working conditions were no better. Dirty, dangerous and loud. The women who worked in those mills lost their hearing young. They became known for lip-reading, and talking loudly with exaggerated facial expressions, like the mill girls of Yorkshire and Lancashire, lovingly caricatured by 20th-century comedians like Les Dawson.

The lipreading was handy. A woman could be working two looms simultaneously, putting her some distance from her nearest co-worker. Mind you, she had little time to chat. She needed eagle eyes on that shuttle. Threads broke frequently, requiring nimble fingers for fast fixes.

All of this made the chances for nuanced workplace conversations about developments in political theory difficult. Things didn’t really improve outside the gates. Most of the workers were female, and despite Dundee’s reputation as a ‘woman’s city’, housework still needed to be done. Mill girls may very well have wanted to start a revolution, but they had to get the tea on first. Then finish the laundry.

‘Great deal of important discussion’

Heckling, at the start of the process, was originally done separately from the looms, mainly by men, working slightly away from the factory floor. In some places, this would be known as the ‘heckle house’ or shop. These men worked physically closer together, giving greater opportunity to explore radical and dangerous ideas of liberty, equality and solidarity.

And the hecklers had a secret weapon, as detailed in Perthshire Courier of 1834: “Some heckling shops in Dundee contain from 50 workmen. Their occupation not noisy, a great deal of important discussion takes place in heckling shops, where a great variety of newspapers are often received, and read aloud.”

Those newspapers could include the radical rags of the age, carrying thoughts and ideas of fair pay and egalitarianism. Dangerous stuff in a combustible environment, which the city of Dundee certainly was. Unrest was never far away. In 1792, inspired by the French Revolution, the city rioted. In an unusual display of fraternity, Dundonians seized and planted an ash tree at the town cross.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey festooned it with ribbons and decorations as the ‘Tree of Liberty’, and cheered when Lord Provost Riddoch danced around it three times, possibly under duress. He got his own back. He had the militia dig up the ‘Tree of Liberty’ and threw it in jail. In Dundee, even the trees could be radicals.

Throughout the 19th century, strikes became common, and hecklers became organised. Mills were closed by workers demanding higher pay. Newspapers observed that these strikes could last for weeks, bolstered by financial aid coming from other workers from as far afield as Glasgow and Paisley. They had begun to create trades unions, a development that rattled the mill owners.

Hecklers in charge

By 1833, the Perthshire Courier notes that mill-spinners were “completely under the control of their hecklers. A delegate is from time to time sent from each spinning-mill to inform the union what stock of dressed flax is on hand… it is then computed what length strike might be necessary to throw the whole establishment out of employment – so that they may determine what… wages may be demanded.”

The next year, the newspapers triumphantly wrote that some mills were introducing steam-heckling machines. They also managed to blame the radical elements in the hecklers for forcing benevolent owners to invest in this new technology. The power of the heckler would be broken, they declared.

It wasn’t. Hand heckling remained a vital part of the process, and the hecklers, tough, organised and opinionated, began to make their presence known in places that excluded women, even Dundee’s formidable Amazons. There are reports of hecklers shouting down pub owners and mill representatives and joining Chartist rallies.

By the middle of the century, politicians started to fear them, and the people who emulated them. The Glasgow Herald of Monday, October 16, 1848, carried the headline “‘HECKLING’ AN MP” above the story of how Mr Archibald Hastie, “the respected representative of Paisley, was subjected to a ‘heckling’ by his Constituents, in the Exchange Rooms, Moss Street, in that town”.

Heckling had arrived, and went on to conquer the world. Dundee is justly famous for its jam, jute and journalism. Perhaps we should also add to that list the powerful voice of the heckler.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.