Book review: The Mack: Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow School of Art, by Robyne Calvert

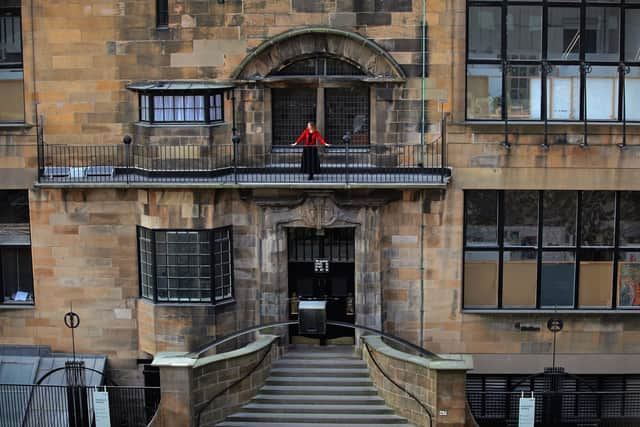

It’s a difficult moment to publish a book about the Mackintosh building. While there’s much to say about Charles Rennie Mackintosh’s masterwork, voted in 2009 Britain’s favourite building of the last 175 years, there’s no escaping the fact that it now lies in ruins following two devastating fires in 2014 and 2018.

Robyne Calvert, a cultural historian now based at Glasgow University, was Mackintosh Research Fellow at Glasgow School of Art from 2015-2021, and her book was originally planned as “a document of the resurgence of the building” after the 2014 fire. Instead, any future restoration is mired in delay and controversy. The Mack, she says, is now “an ephemeral thing, existing somewhere between wreckage and memory”.

Advertisement

Hide AdWe’re on firmer ground with the past, and the central core of the book is a succinct but detailed – and beautifully illustrated – history. The Mack was built in two phases, the east wing and central section in 1896-9, and the west wing ten years later. By this point Mackintosh’s confidence and ambition had grown, leading to an additional floor and inspired design solutions such as the the brick loggia and the “Hen Run”. Mackintosh, however, left little in terms of a paper trail. It’s not him who comes alive in these pages, it’s the Mack itself.

Calvert is clear that the building was not proto-modernist, it was a work of its time, an “amalgam of influences and ideas… uniquely combined”. While there is some truth to the comment made by one critic at the time that its four elevations could have come from different buildings, the contrasts were synthesised in the interior, which flowed despite its many quirks. It was a gesamtkunstwerk – a total work of art.

In no small way, the book is a celebration of the years between 2014 and 2018: the rallying of the GSA community across the world after the first fire, the way the building (as far as possible) became a focus again for creative projects, the wealth of research carried out as part of the restoration. And while the restoration itself – heartbreakingly near completion in 2018 – was destroyed, the research remains, a resource for any future rebuilding.

Calvert does not deny that, after the 2018 fire, “things turned ugly for GSA”. She steers a course through this with care, reporting the facts clearly and, for the most part, unemotionally. Anger is widespread and questions remain unanswered about why the smoke detection system failed, whether the building was appropriately insured, even what caused the fire (investigators found the damage too great to trace the cause).

She concludes that there was “an egregious error… in the protection of this building” but hopes it was – borrowing Mackintosh’s well-known maxim – an “honest error”. The question is not whether the Mack can be restored, Calvert says, and that much is true. But the question of whether it will be remains open.

The Mack: Charles Rennie Mackintosh and the Glasgow School of Art, by Robyne Calvert, Yale University Press London, £35