Art reviews: Art and Design 1890 to 1950 | John Mooney | Caroline Walker

Art and Design, 1890 to 1950, Fine Art Society, Edinburgh ****

John Mooney: Metamorphosis, Summerhall, Edinburgh ****

Caroline Walker: Nurture, Ingleby Gallery, Edinburgh ****

Looking back at the art of the last century, we generally see the two world wars as watersheds. Traumatised by war, what went before 1914-18 and what came after were quite different things, and the same was true of 1939-45. Taking a different approach, however, Art & Design 1890 to 1950 at the Fine Art Society treats the production of art and design in the UK in the years of the titular period as a continuum, which of course it was. History didn’t stop and start but flowed straight on. The frame of reference is broadened, too, by the range of work in the show, from oil paintings, prints and drawings to sculpture, furniture, woven carpets and designs for printed fabrics.

Advertisement

Hide AdThere is, for instance, an early example of the original Anglepoise lamp, designed by George Carwardine and first produced in 1935. A contemporary modernist design by Alfred Burgess Read has a domed metal shade. Both designs reach far beyond the decade of their origin into the post-war world. The same is true of two examples of furniture made in chrome-plated tubular steel, a chair with a black leather seat and and a table with its top in black stained oak. These were hallmark designs of the 1930s, but endured till long after.

One of the most austerely beautiful things here is a rug designed by Gunta Stöltzl in the Bauhaus. Everything in the pattern is rectangular, but because of subtle shifts in alignment, the effect is not static, but lively. In the 1920s, the Bauhaus was the powerhouse of modernist design. But if you look at a William de Morgan tile from c.1890, or an austere design for a rug with trees and hills by Voysey, you can see how the radical Bauhaus designers built on the work of these and other pioneers of the Arts and Crafts Movement. The latter were led by William Morris and the influence of his designs is manifest here in several of patterns for floral fabrics.

There is a rug from the Omega Workshop, too, with a pattern of simple geometric shapes in blue, back and white. Created c. 1913 to 1915, either by Duncan Grant or Frederick Etchells, it is as austerely geometric as the Bauhaus rug, although I suppose a Bauhaus master might think it was a bit sentimental. Instead of a stern mechanical finish, it preserves the freedom of the original drawing. A rug designed by Marian Pepler is as severely geometric as the Bauhaus design, but the title Benin Rug suggests that its inspiration is in Africa, a long way from the Bauhaus.

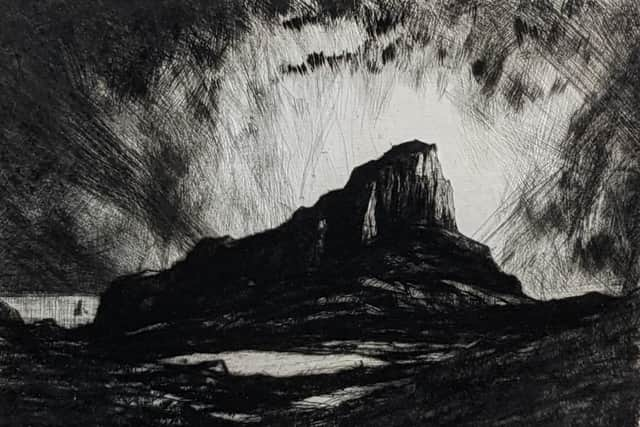

A woodcut titled Southern Landscape by Ian Macnab from 1933 shows similar patterns of geometric shapes in the overall design, although it is a perfectly legible scene. But if this indicates stylistic similarities across different media, there was plenty of variety too. One striking juxtaposition puts a superb etching by DY Cameron, The Scuir of Eigg from 1931, alongside Machine Gods, a woodcut by William McCance from 1930. Cameron’s etching is a grand romantic image, while McCance’s woodcut is an abstraction of machinery, all wheels and pistons and suggesting driving energy. It is halfway between the Futurists in the recent past and Eduardo Paolozzi in the near future. In a different mode, a female nude by JD Fergusson, with her hands raised like a caryatid, manages to be both monumental and sexy, but a nude by McCance doesn’t quite pull this off. Instead it has rather unexpected, formal echoes of the tubular steel furniture.

There are many other things to admire. A real treat is group of three of Leslie Hunter’s Fife paintings. One of them is dated 1923 and all three were painted by the harbour in Largo. They are very small but clearly done on the spot, and they show him at his best and most spontaneous. There is a superb painting of a black woman dressed in blue and gold by Henry Alison, several good paintings by Gillies and some beautiful flower studies by Katherine Cameron. An early watercolour of a windmill by Joan Eardley suggests she had been looking closely at Van Gogh’s Montmartre windmill in Kelvingrove. Altogether it is a rich miscellany.

In contrast to such a time specific show, John Mooney’s work in Metamorphosis at Summerhall seems timeless. Although there are always visual references in his paintings, the formal austerity of his designs can echo the abstract, geometric formality of Gunta Stöltzl’s Bauhaus rug. Mooney’s work was for a long time an admired fixture in the RSA and RSW annual shows. It is a long time since it was seen in a one person exhibition, however, and clearly he has not been idle. There are more than 30 works in this show. They are not dated, but their production ranges over a period of years. Double hung in quite a small gallery, the effect is pretty powerful, but because they are intricately painted and so each very self-contained, it doesn’t seem as overwhelming as it might.

Advertisement

Hide AdMooney paints in watercolour, but defying the loose character of the medium disciplines it into patterns of formal design. He is so precise that you can search and never find a blot or smudge. He also saturates the paint, layer upon layer, to maximise the brilliance of colour. His subject matter consists principally of visual and verbal puns with frequent crossovers between them. A frequent motif is a flat articulated object, a mask, a bust on a stand, but also a whole variety of other intriguing images, including occasionally cut-out letters, but frequently seen from the back as well as the front to reveal them as free-standing plywood cutouts, like painted stage flats or the two dimensional houses in a wild west movie. Texts are usually seen in mirror image and include statements like OhNoYokoOnonono etc..… or Because you are worthless, an array of lipsticks punning on the odious advertisement. Sometimes 40 or 50 diverse objects are arranged in small boxes. One example of this is aptly titled Inventory. Classical columns become rockets, lipsticks explode. The backgrounds of abstract patterns insist that the images exist in a mental space, not an illusory visual one. These are intricate, complex and witty pictures, all painted with exquisite delicacy and brilliant colour.

At the Ingleby Gallery, Nurture is a show of Caroline Walker’s charming, low key paintings documenting the life of herself and her two small children as they interact with the world, especially as it is organised and kept functioning by dedicated women. Several large paintings include Preparing for Laurie II, depicting a woman – the artist’s mother perhaps – preparing for a new baby with baby clothes spread out on a bed. Mini Professors is an indoor scene in a nursery school while Morning at Little Bugs is a scene in an outdoor nursery which one of the artist’s children attends. Smaller pictures include a swimming lesson and weighing a baby. There is also a group of ink and wash drawings that represent a preliminary stage of these more developed compositions. Free and luminous, these drawings are particularly lovely.

Advertisement

Hide AdThe artist set out a while ago to document some of the many, often unrecognised roles that women play in daily life. Her own move into family life and all the interactions that it entails, which is what seems to be what is recorded here, has given her work a new intimacy and immediacy which lifts it above the merely documentary. I am not sure that her pictures warrant comparison with Vuillard or the great painters of the Dutch Golden Age, as is suggested in the blurb, but they don’t need such comparisons. They can speak for themselves.

Art & Design 1890 to 1950 until 20 April, John Mooney until 2 June, Caroline Walker until 1 June