Art review: Graham Rich | Philip Reeves

“Alone, alone, all, all alone,

Alone on a wide wide sea!

And never a saint took pity on

My soul in agony.”

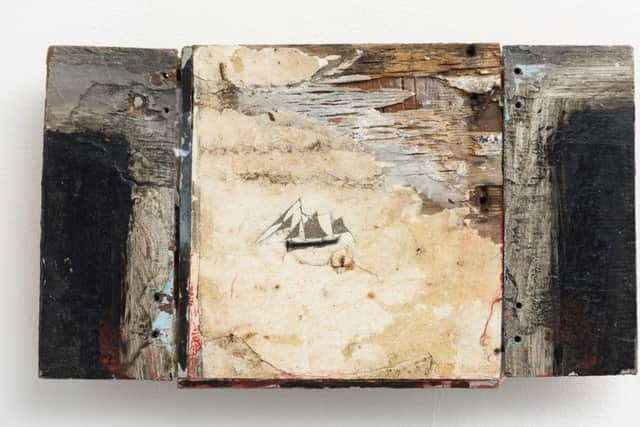

I t was Graham Rich’s work at the Fine Art Society, tiny sailing boats alone in wide spaces, that brought the Ancient Mariner to mind. Perhaps, too, when he wrote those lines, Coleridge himself knew something of the votive pictures that in Catholic countries sailors were wont to hang in churches after some miraculous escape, in gratitude to the saint to whom in extremis they had prayed. These pictures bear some resemblance to Rich’s work and in the catalogue he reproduces an example from the Maritime Museum in Venice. A boat with tattered sails passes the buoy and pier-head that mark the safety of home. Through luminous gaps in the storm clouds above, St Francis and the Madonna and child, whose blessings the Ancient Mariner so conspicuously lacked, look down benevolently on the sailor’s safe return.

Graham Rich: Sailing with Ghosts | Rating: ***** | Fine Art Society, Edinburgh

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdPhilip Reeves: Selected Works | Rating: **** | Open Eye Gallery, Edinburgh

In the catalogue Rich describes how he began to make his ship pictures in 1999 in circumstances where he felt he too needed divine intervention. His wife was very ill. Faced with this emergency, he writes, “the image of a small sailing boat came through me, not from me. I began cutting the boat into found wood as a result of this medical emergency. The eidetic image of the boat was accompanied by a repetitive mantra in my brain, ‘I must sail my wife safely home.’”

He also cites Dutch performance artist, Bas Jan Ader, whose final, perhaps deliberately suicidal performance was a trip across the Atlantic in a 13-foot dinghy. Inevitably perhaps, he never arrived and his little boat was found drifting, empty and half-sunk, off the coast of Ireland. In the catalogue, Rich also includes a photograph taken on an earlier voyage by this Dutch artist which seems to reveal a mystery figure on the deck at what was evidently a moment of extreme danger: a saint to the rescue, or the photographic record of a hallucination? The Ancient Mariner is also haunted by hallucinations of this kind, sometimes attendant upon extreme conditions at sea.

It seems the poetry in Rich’s beautiful paintings and assemblages is deceptive in its apparent quietness and the subject of some of them at least is those in peril on the sea: the loneliness of sailors against the ocean’s vastness and the imaginative resources that are sometimes their only succour becomes a metaphor for the universal human condition. Thus Rich’s tiny, fragile sailing ships, often alone like the Ancient Mariner, against a wide, wide sea, are existential points in the infinite field of space-time. Occasionally, however, there are several little ships in a little flotilla, or a single lonely ship has the company of its own reflection, suggesting calm conditions, although these may not necessarily be reassuring. In one example, flaking white paint suggests a looming iceberg above just such a calm sea, something the Ancient Mariner also experienced: “And now there came both mist and snow,/ And it grew wondrous cold:/ And ice, mast-high, came floating by,/ As green as emerald.”

The supports Rich uses are found materials, usually wood, stained by the vicissitudes of its fate, or with traces of sea-worn paint on it, perhaps even itself the relic of some boat long ago broken up. All that implied but unknown story is crucial to the work and until recently he did not intervene at all beyond painting or cutting a sailing boat or boats into this found surface. Now however he does sometimes work on it, if minimally, adding a scratched shape to suggest a pier, or a stain of white for cloud or light on water, or he introduces details like a pair of swans, or a fishing boat. Nevertheless, the supports always stand for the sea. Indeed, especially in the larger works, in a kind of alchemy his little sailing ships turn inert wood into sea and sky. Thus transformed, the marks on the wood suggest the turbulence of waves and weather, or sometimes of darkening skies. Sometimes, too, random scratches or streaks of paint read like the lines drawn on a navigation chart and so seem to mark the little ship’s progress across the wide water.

If so, there is also a link in this image to one of Ian Hamilton Finlay’s, Little Seamstress, a print made in collaboration with Richard Demarco and one of his best known visual poems. The little ship in the print is a seamstress because she tacks across the water. The line of her wake is the line of her stitching. There is no direct link between Rich’s work and Finlay’s, but the latter loved boats, admired Rich’s work and owned several of his paintings. The artist described to me how a cheque - or at least an Ian Hamilton Finlay work in the form of a cheque originally from Rich himself, but reworked so that it is signed with a sailing boat and sent by Finlay to the artist – was an intervention that persuaded him that the boat was indeed his signature and he should stick with its imagery. Along with the larger works here there is also a wall of small works, tiny, exquisite visual poems of the sea. Finlay was certainly right.

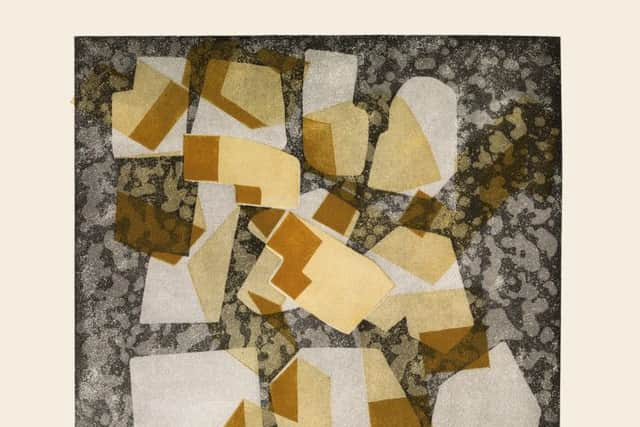

Alchemy is also on view at the Open Eye in the work of Philip Reeves. He really can take base material and turn it into gold. This is what happens in one lovely collage where a sheet of humble, slightly yellowed paper, set off against black by a strip of brown tape, glows like gold. The same thing happens when a sheet of paper roughly stained yellow is set against red, black and scumbled white. Reeves’s imagery seems to evolve from a dialogue between things seen and things found. The seen is always a trigger or a suggestion and is often there in his titles. The found is usually scrap paper, cardboard etc, but he does also incorporate more substantial found objects into his work sometimes, or use them directly in his prints. But whatever he uses, it sets up an internal dialogue among the elements involved and so the work evolves until it reaches, not a point of stability – Reeves was always clear about that – but of unstable equilibrium. Thus what at first looks simple, perhaps only two or three elements brought together, always reveals hidden complexities. This small exhibition is beautifully chosen, too, bringing together a group of lively, light and luminous works.

• Graham Rich until 27 February; Philip Reeves until 17 February