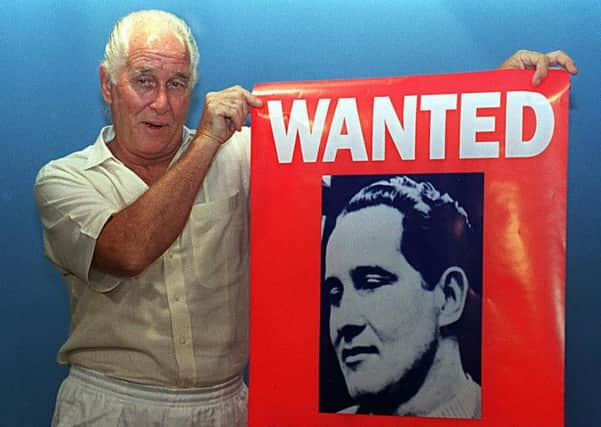

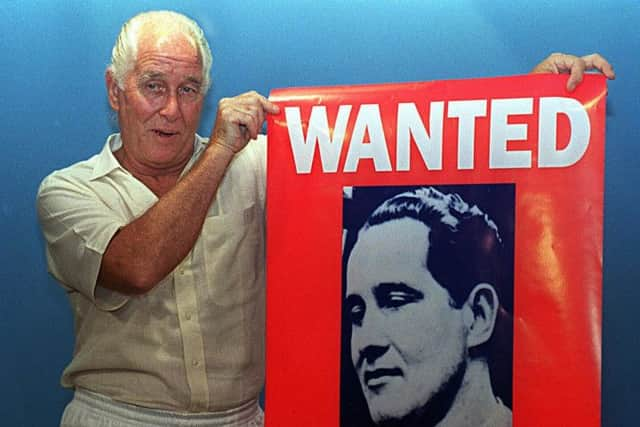

Great Train Robber Ronnie Biggs dies aged 84

To most he was a violent robber whose crime cost a man his livelihood and later his life; for some he became a kind of anti-hero, putting two fingers up at the establishment.

Ronnie Biggs, the Great Train Robber, died yesterday aged 84.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe criminal who escaped prison and spent almost 30 years in Brazil, beyond the reach of the long arm of the law, died at the Carlton Court Care Home in North London.

He had been released from jail on compassionate grounds in 2009, after being crippled by a series of strokes.

His son Michael said yesterday: “I’m sorry to say my dad passed away in the early hours.” Biggs’ death came just hours before the BBC broadcast the first episode of a two-part drama based on the robbery on 8 August, 1963, during which a train driver, Jack Mills, was struck with an iron bar. He died a few years later.

Christopher Pickard, the ghost writer of Biggs’s autobiography, said he should be remembered as “one of the great characters of the last 50 years”. He said his friend was “a very kind and generous man with a great sense of humour” and “one of the first products of the media age, inherited fame while running around the world”.

However, Anthony Delano, who wrote a book about Biggs, whom he met on several occasions, said: “He was a man with no moral compass whatever. He was a small-time crook who probably would have ended up in prison for a greater part of his life anyway. I think he was lucky actually to have so much of it free.”

Mick Whelan, general secretary of train drivers’ union Aslef, said he was sympathetic towards the criminal’s family but added: “We have always regarded Biggs as a nonentity and a criminal who took part in a violent robbery which resulted in the death of a train driver. Jack Mills, who was 57 at the time of the robbery, never properly recovered from the injuries he suffered after being savagely coshed by the gang of which Biggs was a member that night.”

In an interview, Biggs said the coshing of Mills was “totally regrettable”, adding: “I regret it fully myself. I only wish it would not have happened but there’s no way I can put the clock back.”

But Biggs said he did not regret the robbery and, referring to comments made by the judge in the trial, he said: “I’m tot-ally involved in vast greed, I’m afraid.”

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdDespite his monicker, Biggs’ role in the robbery was botched. Biggs, a carpenter who had been dishonourably discharged from the RAF, had the responsibility of enlisting an experienced train driver. The target of the 15-strong gang was the Glasgow to Watford travelling post office which they stopped at the Bridego Railway Bridge in Buckinghamshire by triggering a false red light.

Once onboard, one of the gang, believed to be Ronald “Buster” Edwards, struck Mr Mills, with an iron bar. With his head bleeding profusely from a deep gash, he was dragged to the back of the cabin. However, Biggs’ driver was unable to start the train and was replaced by a still groggy Mr Mills, who was threatened with a further beating unless he moved the train to a prearranged spot.

Biggs then helped load the mail sacks which were discovered to contain £2.6 million in used £1, £5 and £10 notes, the equivalent of about £38m in today’s money, into waiting Land Rovers. The police received an anonymous tip-off and discovered the farm the gang had been using as a safe house.

Thirteen men were eventually caught, including Biggs, but after serving just 15 months, he escaped with three other prisoners using a ladder which had been thrown over the prison wall.

After being smuggled to Paris, where he underwent plastic surgery to alter his appearance, he quietly moved in 1970, with his first wife and three children, to Australia. Five months later, he abandoned them and escaped to South America on a passenger liner using a doctored passport.

Shortly after Biggs settled in Rio de Janeiro in 1971, he got word his eldest son, Nicky, had been killed in a car crash.

Biggs was to spend 31 years in the city he sometimes called his “paradise prison”. He claimed to have slept with more than 2,700 women and had a son, Michael, with his then girlfriend, Raimunda de Castro, a nightclub singer.

In 1981, Biggs was kidnapped by mercenaries, stuffed into a sack marked “live anaconda” and shipped to Barbados, in what they claimed was a “deniable operation” by the British government. Yet it was ill-conceived, as one of the kidnappers alerted the media, leading a lawyer to step in and ensure Biggs’ return to Brazil.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIn 2001, he came back to Britain seeking medical help and was sent to prison to complete the remainder of his sentence.

However, in 2009 he was released on compassionate grounds after suffering strokes and contacting pneumonia.

He had spent the last few years unable to speak and moved with difficulty using a walking frame. His last public appearance was in March when he attended the funeral of his fellow robber, Bruce Reynolds, but he was still able to flick a “V” sign at photographers.

The BBC declined to postpone showing the TV dramas, the first part of which was broadcast last night. Chris Chibnall, who wrote them, said Biggs was not the primary focus and that tonight’s second part dealt with the police investigation into the crime.

According to his son, Biggs wished to have his ashes spread between Brazil and England.

Nick Russell-Pavier: Hero or villain, Biggs has left a lasting mark

No-one could have imagined that a scruffy 15-year-old working class boy standing before Lambeth magistrate’s court in 1944 would become one of Britain’s best-known criminals. Least of all Ronald Arthur Biggs.

Ron, whose mother had died a year earlier, stood accused of stealing. It was the first of many petty convictions and in many ways his life was not unusual. But it became a life less ordinary in the summer of 1963 when he was invited to join a gang who were planning to rob a mail train.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThe raid was dubbed “The Great Train Robbery, The Crime of the Century”. The tale that we all think we know so well is a cartoon caper with loveable rogues and two fingers to the establishment. The real story is messier and darker.

Except Biggs escaped jail in 1965 and went on the run for 45 years, 363 days.

Biggs stole for himself, his family, for a better life, but although he walked away from the raid with the equivalent of nearly £2 million in today’s money, he had robbed himself of his future. Life after the robbery was a forlorn and meagre existence. He was to live apart from his wife and family, whom he’d taken on the run with him to Australia.

The stolen money was too quickly spent on just surviving and staying one jump ahead. Life on the run, trying to make ends meet with inane publicity stunts, was another form of imprisonment, in spite of the Brazilian sun.

Was Biggs a hero or a villain? Heroes are altruistic and do brave things for others. Robbers are driven by easy money, self-interest and only do things for themselves. In perpetrating their crime the Great Train Robbers inflicted violence and terror on innocent people.

It would be perverse to label it as heroism and applaud it. We have an ambivalent attitude to wrongdoing. Society is glued together by moral principle, but we also like the idea of people who don’t play by the rules.

Whatever we feel about Ronald Arthur Biggs, he’s left his mark and perhaps obtained a small slice of immortality.

• Nick Russell-Pavier is author of The Great Train Robbery.