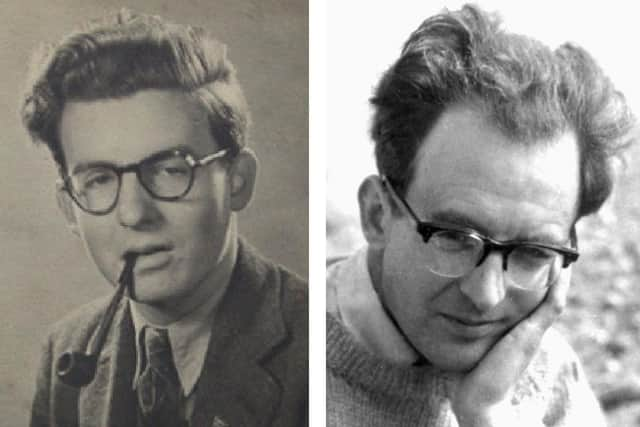

Obituary: Owen Swindale, gifted musician who changed direction to become silversmith

Owen Swindale was a man with many and varied gifts. He was first and foremost a musician: he wrote a standard textbook on 16th century polyphony, he composed and played the piano as well as, at various times, the recorder, horn and violin. He taught harmony and counterpoint for over a decade at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in Glasgow. But he spent the largest part of his life working as a craftsman silversmith on the Isle of Arran, making jewellery with silver and gold and semi-precious stones. He painted, wrote a good deal of excellent poetry and thought continually about the best way for society to be organised. He remained an ardent socialist all his life.

He was born in 1927, the only child of a working-class family in the East End of London. His parents had little money and they moved from one rented place to another. By the end of the first year of the war both of his parents had died and he was looked after by his aunt and became largely self-taught. During the war he discovered and became inflamed (as he put it) with music. Through the Blitz he studied the piano at the Guildhall with Jenny Hyman (he recalled sheltering under a piano during an air raid) and earned a living working in Broadwood’s piano factory and odd-jobbing as a horn player in London orchestras. Soon after the war he met the love of his life, Tessa Engelmann. They courted on Hampstead Heath and married not long after, in 1947. He was 20 and she 18.

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdThey moved to Edinburgh, where ‘ludicrously underprepared’ he sat the entrance exams for the university, and got in. They had a lively social life and a large circle of friends, mostly all musicians. Tessa presented him with two children while he was still an undergraduate and a third shortly after graduating. As money was short, he and Tessa’s brother Ian started a cafe – The Conspirators – which, scandalously for Edinburgh at the time, stayed open until midnight and attracted a lot of customers. He conducted the student orchestra and also made a bit of extra income working as a music critic for The Scotsman from 1954-1961.

By then a fairly prominent young member of the Scottish musical scene, he was recruited by Henry Havergal to teach at the Royal Scottish Academy of Music and Drama in Glasgow. This he did from 1956 until 1970. During this time he wrote his seminal textbook Polyphonic Composition, which was published by OUP and remained in print for decades. Many of his pupils went on to distinguished careers, and many remained lifelong friends. An obituary of one of them, Ronald Walker, mentions “a very different RSAMD in those days with the patrician figure of Henry Havergal as Principal and a complement of often brilliant and sometimes eccentric staff … Owen Swindale was Ronnie's harmony and counterpoint teacher and a considerable influence upon him (Swindale's textbook on harmony and counterpoint was ahead of its time).”

Although his musical career at this stage might have seemed full of possibilities, he became disillusioned with academic life. Among the reasons were changing musical tastes. In his own words: “The work I might have done in composing was inhibited by the change of policy amongst the establishment which went all out to discourage the evolution that was taking place in English music, and replace it with an alien and artificial style imitating the American avant garde – any trace of tonal structure was hissed. Even Beethoven was analysed with a view to possible tone-rows. It was hard to fight, and the trahison des clercs was most painfully apparent. I gave in and shut up; and it took the steam out of my boilers.”

He also became disillusioned with musical scholarship. Doing research, he realised the impossibility of explaining Beethoven’s musical structures in words – though he was adept at explaining to students the varied harmonic and contrapuntal devices used by lesser composers.

During the 1960s, family holidays on Arran provided some relief from the tedium (for him) of teaching. He rebuilt a semi-derelict cottage in Pirnmill, which became a second home for him and his family. It was on Arran that he met the silversmith Mike Gill. Self-sufficiency and the craftsman’s way of life were in the air and with Mike’s example at hand, Owen decided to give up teaching. He and Tessa left Glasgow and moved to Malvern, Worcestershire, where Tessa worked as a chiropodist, providing critical financial security while Owen started making and selling jewellery.

They lived there for ten years, but the connection with Arran proved impossible to break and in 1980 they moved back to the island, buying Mike Gill’s house and workshop, Shawfield, in Whiting Bay, where they lived for the next 35 years. Owen gradually resumed composing and with the help of musician friends including the organist George McPhee (a former pupil), oboists Margaret Malpas and David Cowdy, and recorder player John Turner, much of his music was published and performed, on and off the island. However Owen never regretted his decision to become a silversmith and he often explained how satisfying it was to be a craftsman and to have a connection with the person who was buying the thing he had made. His jewellery, including engagement and wedding rings, must have given satisfaction and pleasure to countless purchasers.

He was relentlessly questioning and struggled to work out the best ways for people to live. Despite having done scientific experiments as a boy, he largely rejected science as a means of understanding anything that seemed important to him but instead looked to his own experiences, the arts and the writings of others for solutions. William Morris and John Ruskin were his heroes.

He died peacefully shortly after being admitted to Montrose House nursing home in Brodick. Tessa had died a few years earlier, in 2016. The family is grateful for the many years of care provided to Owen by the Arran Care at Home team. He is survived by his four children, Nicholas, Iain, Amelia and Mark, and a grandson, Thomas.

Obituaries

Advertisement

Hide AdAdvertisement

Hide AdIf you would like to submit an obituary (800-1000 words preferred, with jpeg image), or have a suggestion for a subject, contact [email protected]

A message from the Editor

Thank you for reading this article. We're more reliant on your support than ever as the shift in consumer habits brought about by coronavirus impacts our advertisers. If you haven't already, please consider supporting our trusted, fact-checked journalism by taking out a digital subscription. Click on this link for more details.

Comments

Want to join the conversation? Please or to comment on this article.